In 1814, the Carbonari resolved to use force to obtain a constitution for the Kingdom of Naples. The lawful ruler, Ferdinand I, was opposed to them, but the king installed on the throne by Napoleon, Murat, joined them in March 1815, believing that the time had come to establish a united and independent Italy. However, Murat was captured and executed in October of the same year, and Ferdinand ascended to the throne once more. In the years that followed, the Carbonari grew in strength and power throughout the Kingdom of Naples, laying the groundwork for a new revolutionary movement. The Carbonari spread from Naples into the neighboring territories of the Church’s States, and society sought to establish itself here as well. In this case, too, society sought to destabilize the papacy’s absolute dominance. The Carbonari even issued a forged papal Brief containing an apparent confirmation of the alliance. Cardinals Consalvi and Pacca issued an edict against secret societies, particularly Freemasonry and the Carbonari, on August 15, 1814, making it illegal for anyone to join these secret societies, attend their meetings, or provide a meeting place for them. Despite this, the Carbonari’s propaganda continued, particularly in the district of Macerata, where an outbreak occurred on June 25, 1817, but was easily suppressed by papal troops ((cf. the important report, of Leggieri, Processo romano contro i congiurati di Macerata di 1817, ristretto presentato alla congregazione criminale, Rome, 1818).

When the Spanish revolution broke out in 1820, the Neapolitan Carbonari took up arms once more in order to force King Ferdinand I to issue a constitution. They advanced from Nola under the command of a military officer, Morelli, and the Abbot Minichini. They were joined by General Pepe and many officers and government officials, and on 13 July, the king took an oath in Naples to uphold the Spanish constitution (cf. Pepe’s defense, Relation des evenements politiques et militaires qui ont eu lieu a Naples en 1820 et 1821, Paris, 1822). Victor Emmanuel resigned the throne in favor of his brother Charles Felix after the movement spread to Piedmont. The movement was crushed and the Neapolitan constitution was suppressed only because Austria intervened and sent troops to Italy.

The Carbonari, on the other hand, secretly continued their agitation against Austria and the governments associated with it. They formed a vendita even in Rome, published the most heinous accusations against the lawful rulers in the press, and won over members of deposed sovereign families to their cause, including Prince Louis, later Napoleon III. On September 13, 1821, Pope Pius VII issued a general condemnation of the Carbonari secret society. The association gradually lost its influence and was absorbed into the new political organizations that sprang up in Italy; its members became especially affiliated with Mazzini’s “Young Italy.”

Giuseppe Mazzini

Now Mazzini was a prominent figure of the Carbonari. In fact, he was an Italian Carbonaro and a 33rd Degree Freemason. By the 1830s, he had established Young Italy, a clandestine movement based on the principle of “Italian unification as a liberal republic.” Despite his use of the term “liberal,” Mazzini’s politics are on the far right of the political spectrum, according to most analyses. To use Lupo’s phrase, he advocated for “class collaboration,” or a vertical alignment of social classes.

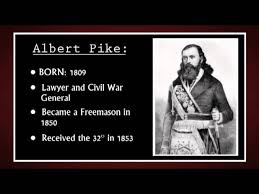

The readers should also know that Mazzini was the director of the Illuminati and that, as Alan Watt had stated in the interview, Albert Pike had trained Giuseppe Mazzini, which is just Italian for Mason. They both were in touch. Albert Pike is the same historical masonic figure, who also was a 33rd degree freemason, occultist, grand master and creator of the Southern Jurisdiction of the Masonic Scottish Rite Order. More about Pike in the future.